A SURVEY OF FILIPINO POETRY IN ENGLISH is an article, written by Luis G. Dato, which originally appeared in the Philippines Herald Mid-week Magazine in April 6, 1932 about his thoughts on classical poetry and the future of the emergence of the new form.

By LUIS DATO

It is a joy to return to Filipino poetry after a separation of three years. One is apt, after the absence, to discover in the beloved object, new charms and new possibilities of charms which in the intimate ardor of the previous obsession one had overlooked, or regarded as of little price, and that is precisely what I feel as I pass on the entire field in review, enlarged as it has been by exuberant new-comers in our garden of songs.

I cannot pose however as a critic with ex catedra authority. There is one man in the Philippines whom I regard as our foremost living authority, A. V. H. Hartendorp, the American editor of the Philippine Magazine, and to him I believe we must turn for a final word on the matter of Philippine poetic values. Mr. Hartendorp suffered much when he loaned his name to Reveries, a volume of poems written by Procopio Solidum, and again to Sunset Dreams, a book of poetry by Baltazar M. Villanueva, both of which we have since learned to relegate to their proper place in the background. There was at least one previous work, one put out by Lorenzo Paredes, and entitled Reminiscences which escaped Mr. Hartendorp’s notice, and on whom he could have lavished his encomiums, for the book contained two poems — My Parting Words and Moonrise which are true gems in the literary history of the Philippines. It was in the course of the preparation of a Filipino anthology of poetry, that I measured for the first time Mr. Hartendorp’s true critical genius in its precise proportions.

Aside from him, there are perhaps a few others, of lesser carat, some of them professors of English in the University of the Philippines, and one or two others in the staff of our Manila newspapers, but their faculties are not so unerring, and are often biased in favor of favorites enrolled in their classes.

In the growth of Philippine poetry, there are two books which are towering landmarks, and which have even determined to a very marked degree, the trend and direction of our poetic evolution. These are FILIPINO POETRY an anthology of our poetry in English since the American occupation down to the year 1924, and M. de Gracia Concepcion’s AZUCENA, published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons in 1925 . They have induced much creative work and that alone establishes claims to our notice; in spite of the discouraging attitude which the Philippines Free Press had put on against the poets, more poetry was written after 1925 than all the previous years combined. The Free Press not only snobbed poetry; it also time and again by direct statement or by policy became mainly responsible for the hallucination current among short-story writers here that the short-story is the whole and only chunk of cheese in Philippine letters, which is not so by a far shot. To date, the most effective writing done by Filipinos in English is in the realm of the essay. The next best thing that has been accomplished is in poetry. The short-story comes a poor third, and surpasses only one branch-the drama.

Undoubtedly the best poetry has appeared in two publications, the Philippine Collegian and the Philippine Herald. Next in record come the Woman’s Home Journal, Woman’s Outlook, Ateneo Monthly, perhaps the Varsitarian, organ of the Sto. Tomas University, and above all, of course, the Philippine Magazine. The Philippines Free Press has lately turned to poetry again, but aside from the reprints, it has published practically nothing worth mentioning. The Tribune is only a bit better.

And now a word on the poetry itself. The work previous to 1924 had a decided Spanish strain, which we did not notice perhaps in the beginning but which we now see standing apart like a foreigner in contrast to the recent poetry. One finds this in many of the poets from Maramag to Mendez, to mention only two; no one can of course say with any amount of reason that these poets are Latinized; they are, in conception and expression very modernly English, but as we take the newer writings after Azucena by way of comparison, the contrast does not escape us. That school has apparently written its concluding chapter; among the new poets it has no important adherents, except in the renascent, and tutored poets of the Ateneo de Manila.

The English influence, always intertwined with the Spanish in the older writings, roots itself more firmly in the new. There is however an added difference. Carl Sandburg, Amy Lowell, Walt Whitman, and the current poetry magazines have influenced the new poets almost to the exclusion of the old masters. Very few of the new poets have any inspiration from Tennyson, Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth and Poe, to the extent that the older poets had, and this explains why, in the appeal to the vital emotions in refinement in sentiment, and even in the sense of form, the older writers maintain an inaccessible superiority despite a lesser familiarity with English idiom. Free verse has been the achievement of the new poets mainly, and this sometimes against intention.

There is much to say of course in defense of free verse. But free verse is immoral, atheistic, nihilistic, violent, and art is not built by a refusal to submit to the exigencies of medium. Great art has been written only under the lash, the poet slaving for his task-master, meter, or chafing under the restraint, but in every case limiting the liberty of his creative power to the discipline of the rules. It might be said that free verse is poetry because like poetry it has rhythm; but even oratory has rhythm, and yet it remains prose, not poetry. Poetry to be poetry must not have rhythm alone but rhythm of a definite kind — rhythm achieved through meter. Amy Lowell, and the rest of the gang of colorists futurists, imagists, and indeterminists to the contrary.

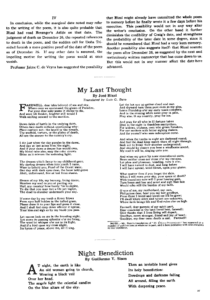

Let us take a current example of our free verse productions, to see the point:

Shades of Night

By Angela Manalang

A silent stranger Waits in the forest by the lake Death has come Into the woodland Where the creek moans on. Where the northwind scatters dry leaves. Sisa is no more. The soul of Sisa writhed to-night Into the creeping shadows of a moondown; It will be beautiful so, Even as in her lonely madness It trembled Through eyes alive yet unseeing, It fluttered Through songs unmeaning and sad. The darkness, dappled and tender, Flits close to the baliti; To the stark form that lies there in the halo Of silence eternal. Tonight Elias rests…. By the streamlet where the cold moon Tiptoes softly on the sand, By the bare tree where the dim wraiths Twitch and spurt m riots mad; Elias rests eternal, For the dawn has fallen And his blood-drops on the lone trail Shine thick and purple As the carmine fire of life Blazes off to another sphere. Pile high the burning faggots! No gaudy tombs to mark the fallen But the fire in ragged crimson. No hooded fiend to snatch the shrouds away, But the smoke in whorls voluptuous.

Disregard the inversions, which sound like a Frenchman ‘s pleasure immense or ladies respectable, and straighten the chopped lines into decent sentences, and what do we find — Prose. A page from the Social Cancer, in better shape perhaps than the translation, but still prose.

PROSE IN FILIPINO POETRY

Jose Garcia Villa is our foremost example of the school of free verse in its extreme form. He is our only example of one who has entered poetry “free” and remains free, but taking all his work by and large we find him deficient of the finer things in poetic writing. M. de Gracia Concepcion’s latest free verse does not rise to the levels of his previous writings; Angela Manalang has returned to the romantic poets which had been her early inspiration, and as for the others, their work falls of their own weight. The exactitudes of meter are learned patiently and obediently, and if a neophyte finds them irksome, his field is not poetry. There are fields where his radicalism and non conformity are wanted. Fortunately much of the revolt against the tyranny of form is based on ignorance of such forms or on pure indolence, and a course in Spanish poetry or return to the old English favorites would do wonders. One cannot imitate inferior models, and surpass those whose wagons have been hitched to the stars.

The selection of wrong authors is very devastating in view of the fact that the new writers are much younger in years and in experience than their predecessors. It is true that they put on an air of cynicism and sophistication, but the fact always stays that they are not sure of the life they are warbling about. One cannot warble unless one has lived and experimented extensively with Moses on the Commandments and poetry can not be great poetry while sophistication continues to run ahead of sin. One cannot write unless one has known satiety, debauchery, and the intimacy of desire, and can remember them “in moments of tranquility”. That is the whole reason why it is so sickening to hear the poets write of love and woman. They know neither one nor the other, and, while some seem to see sentimentality, I see only ignorance. Love and the sentiments always can bear repetition; they are the stuff out of which all poetry is written; it is unfamiliarity with them, and the writing in spite of it, that nauseates.

Yet the new poetry has its merits. I have noticed a wider range of words, and a greater panoply of images in it than in the previous period. It is more objective in other words; it conjures more visual images. Notice for example the following selections:

Ways of A Tree

By Amador T. Daguio

These are the ways of a tree at night: A woman weeping, weeping, Pulling her long and tattered hair, Weeping, pulling her hair in the dusk. A little innocent child Holding the Moon-Bowl, Laughing, laughing as a brook laughs, Sipping broth.

Little Green Acacia

By Fidel de Castro

When the nights are warm and the moon is dead,

I want to lie clown on the wet grass

Where a green cloud of acacia leaves

Hangs over the lake.

l love to watch the leaves falling.

I will wait for you to gather me in your arms…

I am a bunch of flowers then, with soft brown petals.

You shall run your fingers in my hair to make me sing;

And my songs -- I want them like the leaves falling

And ruffle the waters of your dreams.

Song of the Pasig Boatman

By Conrado S. Ramirez

Jump into my banca, my own little bride,

And ride we together the Pasig's brown tide;

Gather your saya and lay your white feet

On the cool zacate I cut for your feet.

Take up the guitarra and sing me a song

Of home and rice field where love tarries long,

The while on the waters that lazily flow

Our banca is borne to where hyacinths blow.

And thus we shall ride, O my own little wife,

The currents and whirls of the river of life,

Gather the blue hyacinths as we drift slowly by,

And float out to heaven on songs when we die.

The Bamboo

Anonymous

The bamboos droop in the hush of night, Huge ferns that dream in the ghostly light, I hear them ask the wind, ''Where are The two we hid when the .moon was bright"

Literature

By Horacio de la Costa

You ask me what it is. It is the thunder Of singing centuries, the fallen gleam From minds immortal that with breathless wonder Strode. wood-paths, faery-foliaged, of the Dream; As ancient as the stars, and yet as young As this dawn's rose, or thrill of bells just rung.

Strength

By Conrado V. Pedroche

"Without, there was the passion Of the angry elements; The min beat wildly, wildly, On the window-panes. An ugly lightning forked Across the sky and split And slashed the mighty void. A rock b,y the sea Stood silent, unmoved. The rain and waves beat Upon its craggy breast In the crimson fury Of their tensile strength -- But the rock stood unmoved, And it laughed, laughed.

I Did Not Know

by Leon Ma. Guerrero, Jr.

I did not know why God made flowers, Why He had sprinkled starlits on the land -- I dreamt in dimly-scented bowers, And did not know what purpose moved His hand Shy violets and lilies slender, The splendorous burst of orchids as they fade The strangely scented, strange tender, Why was all this perfume bower made? And then, the other clay I saw You in your garden·-now I ask. no more I saw the flower in your hair let low, And then I knew what God made flowers for.

Heart’s Desire

By Conrado Ramirez

I wish I were Acteon and behold Fail Artemis disporting, free of dress, In some secluded woodland pool; caress With lingering gaze her hair of woven gold; And envy deep those drops that, clinging, mold Themselves to those twin breasts of loveliness. What if I die of it? Tho sight will bless My soul loner after I am dead and cold. For he who lives and sees but life's drab front Drags through the centuries a soul born dead, While he who lives, though briefly, to affront Divinity, when it, ungarmented He spies in through a screen of woodland flowers, Finds happiness the balm in dying ours.

Secondly, there has been less inclination towards moralizing than in previous years. Poetry is art and feeds on the emotions evoked by the senses; the moment it turns to God it becomes religion; and while it may point to the salvation of our souls it becomes a curse and a burden to all true poetry. Milton’s epics are great not because they teach, nor even because they deal with divinity; they have become immortal in spite of both. Poetry is pagan, not moral and many a good motif for art is marred by the itch to preach the gospel. We are much too fed up with gospels just now, and, if messianic delusion beckons us with a call to regenerate mankind, the Muses were better left alone to their own sweet selves.

Thirdly, there has been also a drift away from assault and satire on women. Poetry is gallant; it does not subsist on an animus furandi against the fair. Poetry lives on love, and love is nothing but the worship of woman. The great poets have been consecrated to woman; to desecrate her has been the patrimonial province of the philosophers.

Finally, there has been a refusal to compass the comic in verse. The purpose of the humorous poet is perhaps laughter, but one never really laughs at the result. For poetry is essentially tragic; it subsists ts on tears and melancholy; it is always pervaded by a morbidity that is alien to laughter; it sees sorrow even in joy. It is as if the Author of Creation, after the hours of Providence, had paused in his miracle and surveys with still, lonely eyes the futility of his world. There is an inward weeping in poetry that turns instinctively away from the bizarre and the vulgar, and laughter and humor are essentially animal and vulgar. The moment Momo laughs, poetry, like the divine essence, escapes and leaps into the sky.

What of the future? There is naturally to be expected a maturity in our poets as the years increase their store of experience. When that time comes, there will be more sincerity in their lines. They have shown an aptitude for a choice of words; life will in turn be kind, and give them an aptitude for a choice of feelings; one is only a step to the other, and when the heart has caught up with the imagination, our garden, now languishing with pale flowers, will blossom forth into the happiest spring.

And with depth will come variety. Our poetry to-day is ridden with simplicity. Our poetry is still primitively free from complications which are the spice of maturer culture. Our pattern at best arrive only at dualities, — pain and pleasure, love and hate, joy and sorrow; we have not caught up with the complexity which makes situations evoking in other countries a dexterity and a morbidity which make their literatures our contact “with the best that has been said an thought in the world.”