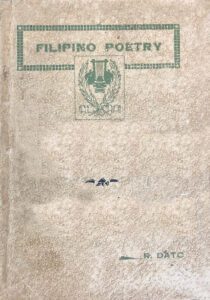

In February 1925, after the recent publication of the first anthology of Filipino poets in English, “Filipino Poetry”, a 19-year old, University of the Philippines student, Luis G. Dato (“Bikol of Baao, Camarines Sur”) wrote the essay, Filipino Poetry, as a survey and an in-depth review of the book. It also expounded on the local production of verses, criticisms, and the history and future of poetry in English. Utmost gratitude sent to the National Library of the Philippines for the digital copy of this archive.

By Luis Dato

We cannot exactly tell just when the Filipinos began tuning the lyre, and invoking the Muse that so nobly inspired Keats and Shelly and Poe to bring forth into the world entrancing measures of delightful verse and poetry. To say with any amount of decisiveness and finality that Filipino-English poetry did not precede and was only consequent to the American occupation of 1898, is precarious, and will afford much room for questioning and doubt. That such men as Rizal and Luna, who sojourned a long time in European countries, and had all the opportunities and some inducements to study and master the language of Shakespeare, had in their leisure hours attempted at composing English verse is a tenable possibility, remote as it may be. For our purpose however, and in lieu of our scanty knowledge of the life and efforts of Filipinos abroad, or educated abroad, before the Americans came to the Islands, it were well to begin our study and view of our English poetry as it sprang up and thrived under American auspices.

Hispanic Influence

Let us at this point take a comparative estimate of our poetry in English and our poetry in Spanish. It is well-known and unchallenged observation that Filipino-Spanish poetry both in matter and manner is superior and more highly developed than the English. Several reasons are set out to explain this fact. In the first place, the Spanish language has been closely connected with Filipino life for a period of nearly four hundred years. That eventful though unprogressive span in our history which began with the advent of Magellan in 1581, and terminated in 1896, entailed much social intercourse — the conquest of the weak tribes and their subjection to the ways and customs and language of the conquerors, commercial and agricultural contact and exchange, religious conversions and missionary work, marriage, and finally the ever increasing flow of Spanish immigrants and sight-seers who came over to the Orient, all these were part and parcel of the semi-cosmopolitan though primitive life of the Filipinos during the Spanish rule. In short, the advantage of years and duration in favor of the Spanish, has been thought sufficient to explaining less healthy and less flourishing growth of Filipino-English poetry and literature. When we consider however that under the American regime, the English language has been made the language of the public schools, and in many primate educational institutions, and that it has been given all the aids and encouragements possible in order that the extension and implantation of the “mother tongue” be more rapid and thorough, and when we consider further that in this age of activity and growth, there is much more social and political intercourse between sovereign and subject, we begin to ask whether there is something else, something more vital and essential than the mere accident of time, which must explain the abject disparity in growth and development of poetry in English and Spanish.

I would advance two reasons. First, the lack of interest in literature and true culture only too manifest in the majority of the Americans who come to the Philippines. This is especially true of the new-comers as contra-distinguished from the “old timer.” Business and industry engross their minds and leave them little leisure and interacts even less in the art or metrical composition. Second, is the fact that the Spanish is more akin and natural to the psychology and life of the Filipinos. This is because Spanish blood runs almost too profusely in the veins of the Filipino, particularly so with the upper and well-to-do classes, who, it is needless to say, are naturally more inclined and disposed to the study and cultivation of culture, of science, philosophy, and the arts — and hence of poetry. Thirdly, the Spanish language is the expression and result of an environment directly north of the tropics, the “Mediterranean” and hence is related more intimately with the life and environment of a tropical country like the Philippines

Be this as it may, it is nevertheless fact that Filipino-English poetry has come in the Philippines to stay, and that the wealth of poetic composition is rapidly and steadily accumulating. No part of the Philippines today cannot boast of some singer in English who in the warm and fervid hopes of his countrymen, will some day give expression to the yearnings and heart-beats of a long-repressed desire and passion poetry and song, and carve for himself a niche in the select hall of English bards in the Orient.

Worthy of mention are the names of Fernando Maramag, Mauro Mendez, Procopio Solidum, the romanticism of whose poems reminds us of the early Cavalier poets of England in the days when Puritanism and Milton were yet unborn and were unconceived.

To point out a particular age in English poetry that will correspond to this formative period of our literature, is indeed difficult and almost impossible. Ours is an age of preparation, and if we take this point of view, Chaucer and his unsung contemporaries may have made up that age in early English poetry corresponding to ours. And yet to say that counterparts is indeed erroneous when we examine the subject-matter. Chaucer wrote poems that were semi-narrative in nature and which had a broad range of subject. His Canterbury Tales for instance were a picture of some noteworthy personages of his day, and a narration of their deeds and virtues. On the other hand if we examine the poems which Filipinos have to offer we find a decided absence of the narrative and a very meagre and insufficient interspersion of the descriptive element. This descriptive element found is largely subjective, and what objective element is there, is often monotonous is the narrowness of subject, in the all too apparent similarity of personal attitude and expression, and in the impression of vagueness and generalization as against conciseness and detail.

Native English Poetry

“Filipino Poetry”, a collection of Filipino poem recently published, and which to all intents and purposes may serve as a specimen of native English poetry, is significant in two respects. First, it is the first attempt to publish poems which in the compiler’s estimate are the best literary productions of Filipino poets. Hitherto little attention was paid to the constantly growing body of local English verse, and not a stop was taken at all to compile them into one volume with a view to present them to the general public for comments and criticisms. The collection contains 89 poems and are the productions of 44 authors. Secondly, the compilation, consciously or unconsciously truly representative both in language and subject of the poems published or unpublished, which constitute our first offering to the Muse. The publications of Ledesma, Solidum and Baltazar, are defective in both these respects. The poems therein contained are indeed well worth praise and favor, and speak highly of the literary of talent of their authors. They augur a bright age in Filipino-English literature, which sooner of later is bound to come. Of special consideration and merit, are some of the lyrics of the Visayan Solidum which bespeak of the poetic sentiment of youth, and the happy-go-lucky disposition the Filipino.

Let us have a glimpse of the poems included in “Filipino Poetry”. What strikes us at once is the subject matter. We find that out of the 89 poems, 33 are love poems, or more specifically the love of woman for man and man for woman; 17 are nature poems, 19 sing of emotions other than sexual love, filial love, joy, sorrow, hope, regret; 7 are patriotic hymns and poems. The remaining 16 are of themes allied to the rest. There is very little of the grave and philosophical in Browning. We find two poems which are satirical, one of which reminds the Philippines Free Press, a weekly which originally published it, of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Vampire”.

With respect to the meter and rhyme, the same regularity of style and uniformity of form is apparent. Rarely do we come across non-iambic verse. With the conspicuous exceptions, Maramag, Serrano and Chavez, all the authors suffer from a lack of initiative and effort to the dactylic, trochaic, and anapestic. In the stanza construction there is much more originality and less restraint. Here we find a freer imitation of all models, ranging from the Tennysonian to the Spenserian stanza, the unconstrained spirit of which reminds us of the revolt against the classical, rigid and measured verse of Alexander Pope.

Finally, we notice a very conspicuous feature. The poems are entirely lyrical, and this trait is true of poems not included in the collection. We have reason to doubt if there is at all in piece of written poetry that with every laxity of criterion may be called narrative or dramatic. This is surprising to most of us who are so well acquainted with the wealth of erotic poetry, which has highly developed narrative element. The tale of witches and unseen spirits, the long and fanciful story of wild adventure and exploits of dead ancestors and long-fought battles, that are distinctive of the vernacular literature are nowhere to be detected in the English, and only imperfectly developed in the Spanish literature of the Filipinos. I will not seek to explain the whys and wherefores of the case, however, suffice it is to say, that with a more intimate and thorough acquaintance of English, and more patient artistic intervention, we cannot say why with such a very fertile imagination and a rich field of narrative and historical material, not to say of myths and fables, the Filipino will someday be able to write dramas in verse, and recount the deeds and valor of his warlike forbears.

The handicap of language will for years continue to be a stumbling-block to the dreams and aspirations of many a Filipino. Insufficient vocabulary, misuse and abuse of words, the need of new words to suit an environment quite distinct from the temperate belt, and finally, the difficulty of attaining fluency of diction and expression. All these obstacles must be mastered before he can write real poetry, and make for himself a name in English literature. In the meantime, he needs encouragement and help. Criticism there must be, but a criticism that must spur him on, and awaken his latent faculties, not restraining and stunt them by too rigid standards. Like a new-sown seeds Filipino-English poetry needs light, moisture, food, and space, not the pruning of the gardener. Our criticism must be sympathetic in the same way that our expectations should be modest and restrained. Ours is not so much a need of an Edinburgh Review, as of anew Tatler and Spectator. We may not produce a Keats or a Shelly, but matters? Has it ever said that from the land of the toboggan there leapt a morning lark, winging in song and rapture, flooding the air with “measures of delightful sounds.”

TO LEONOR

I would my eyes could see

If hers were black or gray,

Her smiles were all to me

Sweet roses blown in May;

Yet all alone we stray,

In vales of love to stay

Can hear the melody

Of poetry in song;

My heart is telling me

That it will not be long,

When all her charms divine

Will be forever mine.

— The 1924 Clarion, University of the Philippines High School

Among the Hills

I used to watch the sunrise glow

That set aflame the eastern skies,

My lips in songs did freely flow

As thoughts went fleeting with my sighs.

I’ve lived through storms and smiles and tears,

And seen familiar faces die,

Ah, these, my weary youthful years

Are fraught with shades of dreams gone by.

And yet when once again I see

The glory of the purpling hills,

My dying heart revives to be

A spring of love and lover’s thrills.

My mind in youth did ever roam

Across the mountains and the dales,

And now my heart has found a home

Among the eastern hills and vales.

— Filipino Poetry, Rodolfo Dato